John Shirley was cyberpunk's patient zero, first locus of the virus, certifiably virulent. A Carrier. City Come A-Walkin' is evidence of that and more. (I was somewhat chagrined, rereading it recently, to see just how much of my own early work takes off from this one novel.)

Attention, academics: the city-avatars of City are probably the precursors both of sentient cyberspace and of the AIs in Neuromancer and, yes, it certainly looks as though Molly's surgically-implanted silver shades were sampled from City's, the temples of his growing seamlessly into skinstuff and skull. (Shirley himself soon became the proud owner of a pair of gold-framed Bausch & Lomb prescription aviators: Ur-mirrorshades.) The book's near-future, post-punk milieu seems cp to the max, neatly pre-dating Bladerunner.

So this is, quite literally, a seminal work; most of the elements of the unborn Movement swim here in opalescent swirls of Shirley's literary spunk.

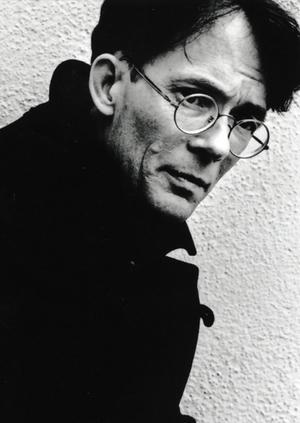

That Oregon boy, with the silver glasses.

That Oregon boy remembered today with a lank forelock of dirty blond, around his neck a belt in some long-extinct mode of patent elastication, orange pigskin, fashionably rotted to reveal cruel links of rectilinear chrome spring: "Johnny Paranoid," convulsing like a galvanized frog on the plywood stage of some basement coffeehouse in Portland. Extraordinary, really. And, he said, he'd been to Clarion.

Was I impressed? You bet!

I met Shirley as I was starting to try to write fiction. Or rather, I had made a start, had abandoned the project of writing, and was shamed back into it by this person from Portland, point-man in a punk band, whose dayjob was writing science fiction. Finding Shirley when I did was absolutely pivotal to my career. He seemed totemic: there he was, lashing these fictions together and propping them in the Desert of the Norm, their hastily-formed but often wildly arresting limbs pointing the way to Other Places.

The very fact that a writer like Shirley could be published at all, however badly, was a sovereign antidote to the sinking feeling induced by skimming George Scithers' Asimov's SF at the corner drugstore. Published as a paperback original by Dell, in July 1980, City Come A-Walkin' came in well below the genre's radar. Set in a "near future" that felt oddly like the present (an effect I've been trying to master ever since), spiked with trademark Shirley obsessions (punk anti-culture, fascist vigilantes, panoptic surveillance systems, modes of ecstatic consciousness), City was less an sf novel set in a rock demimonde than a rock gesture that happened to be a paperback original.

Shirley made the plastic-covered Sears sofa that was the main body of seventies sf recede wonderfully. Discovering his fiction was like hearing Patti Smith's "Horses" for the first time: the archetypal form passionately re-inhabited by a debauched yet strangely virginal practitioner, one whose very ability to do this at all was constantly thrown into question by the demands of what was in effect a shamanistic act. There is a similar ragged-ass derring-do, the sense of the artist burning to speak in tongues. They invoke their particular (and often overlapping, and indeed she was one of his) gods and plunge out of downscale teenage bedrooms, brandishing shards of imagery as peculiarly-shaped as prison shivs.

Mr Shirley, who so carelessly shoved me toward the writing of stories, as into a frat-party swimming pool. Around him then a certain chaos, a sense of too many possibilitics—and some of them, always, dangerous: that girlfriend, looking oddly like Tenniel's Alice, as she turned to scream the foulest undeserved abuse at the Puerto Rican stoop-drinkers, long after midnight in Alphabet City, the visitor from Vancouver frozen in utter and horrified disbelief.

"Ignore her, man," J.S. advised the Puerto Ricans, "she's all keyed up."

And, yes, she was. They tended to be, those Shirley girls.

I look at Shirley today, the grown man, who survived himself, and know doing that was no mean feat. A cat with extra lives.

What puzzles me now is how easily I took work like City Come A-Walkin' for granted. There was nothing else remotely like it, but that, I must have assumed, was because it was John's book, and there was no one remotely like John. Fizzing and crackling, its aura an ungodly electric aubergine, somewhere between neon and a day-old bruise, City was evidence of certain possibilities which had not yet, then, been named.

It would be a couple of years before whatever it was that was subsequently called cyberpunk began to percolate from places like Austin and Vancouver. Shirley was by then in whichever stage of a sequence of relationships (weII marriages actually; our boy was nothing if not a plunger) that would take him from New York to Paris, from Paris to Los Angeles (where he lives today), and on to San Francisco (hello, City). He gave me vertigo. I think we came to expect that of him, our tribal Strange Attraction and blinked in amazement as he gradually brought his Ilife in for a landing. Today he lives in the Valley, writing for film and television, but for several years now he has been rumored to be at work on a new book. I look forward to that. In the meantime, we have Eyeball Books to thank for re-issuing the Protoplasmic Mother of all cyberpunk novels, City Come A-Walkin'.

—Vancouver, BC March 31, 1996