What is love? What is life? What is death? We're in the midst of life; we're all going to die; we all have had experience of love, or we think we have. Do we really know what any of these things are? And, equally important, do we know how to ask the questions so that we can have some hope of finding the answers?

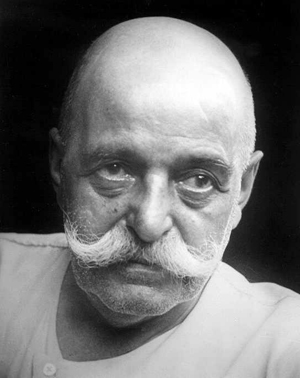

There was a man who provided a body of

ideas which both asked the questions and

foreshadowed the answers. Some answers he

gave forthrightly, and these, if true, are

very startling indeed. This man was born in

Russian Armenia, probably in 1866, and died

in 1949, in Paris, whence he had led his

followers to escape the Bolsheviks and the

murderous chaos of the Russian Revolution.

His name was George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff. He

was, some said, a mystic; he was surely a

philosopher, and a teacher. He spent decades

traveling Asia Minor and the far East seeking

real answers to real questions. Why are we

here? Is there a God? What happens after

death? Are there higher levels of being? In

his Seeking, "Gurdjieff was utterly possessed

by his aim," says his biographer, James

Moore. "Every atom of stoicism inculcated in

him by [his father] was mobilized."

There was a man who provided a body of

ideas which both asked the questions and

foreshadowed the answers. Some answers he

gave forthrightly, and these, if true, are

very startling indeed. This man was born in

Russian Armenia, probably in 1866, and died

in 1949, in Paris, whence he had led his

followers to escape the Bolsheviks and the

murderous chaos of the Russian Revolution.

His name was George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff. He

was, some said, a mystic; he was surely a

philosopher, and a teacher. He spent decades

traveling Asia Minor and the far East seeking

real answers to real questions. Why are we

here? Is there a God? What happens after

death? Are there higher levels of being? In

his Seeking, "Gurdjieff was utterly possessed

by his aim," says his biographer, James

Moore. "Every atom of stoicism inculcated in

him by [his father] was mobilized."

In the course of his years of seeking, Gurdjieff fell ill with some of the most pugnacious micro-organisms the East could muster; and more than once he was grievously wounded by stray bullets, as he skirted the edges of wars and revolutions. He spent years in monasteries in Central Asia, including a spiritual community in the mountains of Bokhara, the Hindu Kush of Afghanistan; he was apparently in close contact with mystics tucked away in the esoteric circles of the Russian Orthodox orders; he studied in Tibet and India. Eventually he returned to Russia, and found students in Moscow and St. Petersburg, not least of these the famous PD Ouspensky, author of Tertium Organum and a partial exegesis of Gurdjieff's system, In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching. Ouspensky later broke with Gurdjieff, and formulated his own (but highly derivative) version of the teaching. Both he and Gurdjieff called the system The Fourth Way.

It seems likely that some of Gurdjieff's ideas sprang from his own brilliant powers of observation, investigation and syncretization. But there are Christian mystics who claim Gurdjieff's teaching is exposed Christian Mysticism. There are Sufis (Islamic mystics) who claim that it is essentially a Sufi teaching. One Sufi teacher told me that Gurdjieff was preparing the West for Sufism; possibly some of Gurdjieff's adherents feel that Sufism was preparing the world for Gurdjieff. Others intuit that the core of his teaching derives from a mystic school that predates all known religions and sects; a teaching that may be the taproot of all esoteric teachings. Whatever its origins, Gurdjieff's "unknown teaching" is vast, complex, many layered, and yet, somehow, tellingly consistent, from layer to layer; profoundly all of a piece. In light of this resonant consistency, there is perhaps no hubris in Gurdjieff's having titled his cycle of books: All and Everything.

Despite parallels in other esoteric traditions, Gurdjieff's teaching is a special balance of Western rationality and Eastern gnosis. Gurdjieff ridiculed occultists, and warned about charlatanism. Gurdjieff scholar and Professor of Philosophy Jacob Needleman asserts, "For Gurdjieff the deeply penetrating influence of scientific thought in modern life was not something merely to be deplored, but to be understood as the channel through which the eternal Truth must first find its way to the human heart." Gurdjieff asked that his students verify, repeatedly, the reality of their esoteric perceptions. Since we're in a constant state of self deception anyway, he knew how easily— indeed, how inevitably—the imagination would distort esoteric work. "In most cases," Gurdjieff remarked to Ouspensky, "what is called 'cosmic consciousness' is simply fantasy, associative daydreaming connected with intensified work of the emotional center... a subjective emotional experience of the level of dreams." As he told his students at his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, "If you have not by nature a critical mind, your staying here is useless."

A caveat. Gurdjieff drew a sharp distinction between knowledge, in the ordinary sense, and understanding. Understanding, he maintained, real understanding, requires a significant degree of inner being. A computer cannot process certain things without enough RAM; a man cannot understand certain ideas fully unless he has enough sheer Being. And some ideas must be understood with one's whole being.

I, personally, understand little. I can't hope to convey more than faint shadows of these ideas and I make no testimony as to their rightness, except to verify that Gurdjieff's ideas resonate with a kind of philosophical verisimilitude almost without parallel.

Common sense supposes that to understand why we're alive—what constitutes the cosmos and our place in it—we ought to start with ourselves. We ought to know ourselves; this was the advice of the classic philosophers—who seemed to understand that it was easier said than done.

Under the usual conditions, Gurdjieff bluntly informs us, we cannot know ourselves, for the simple reason that we are asleep. We are asleep, even when we imagine that we are awake. Man is a machine, Gurdjieff tells us, with characteristic unsentimentality, an automaton of reactions and reactions to the reactions. We imagine ourselves building, creating, moving alertly through the world: we are kidding ourselves.

We are, says Gurdjieff, lost in waking dreams and rigorously tracked neurotic fixations; when we think we are "doing" we are simply caught up in complex, fantasy-tinged reacting. We are asleep. We are not free.

There are three traditional paths to awakening. The first Way is the way of the fakir, demanding physical control and excruciating asceticism; the second is the Way of the monk: the way of devotion, faith, the heart; the third is the Way of the yogi: the path of knowledge, of mind. Gurdjieff's own Fourth Way combines elements of the first three, and is further distinct in that it calls its practitioners to work within themselves while functioning in the ordinary, workaday world. It requires no monastic withdrawal from life—ordinary life is its resource, its basic material. "I wish to create," Gurdjieff wrote, "conditions in which a man would be continuously reminded of the sense and aim of his existence by an unavoidable friction between his conscience and the automatic manifestations of his nature." In ordinary life each and every encounter, lived consciously, can teach us something about ourselves.

Gurdjieff called us "three-brained beings", each "brain" corresponding to an inner center: the intellectual center, the emotional center, the body-ruling instinctive/moving center. Each of these three centers is divided into sub-centers, for example, the intellectual segment of the instinctive center, which does most of our so- called "thinking" for us. Much of our "thinking" is simply a lower center's mis-use of intellectual faculties, a squandering of inner energies in desire-based brain activity. All our Centers are similiarly imbalanced. The Fourth Way calls us to work on all three Centers at once, harmonizing them into one conscious, evolving being. "The modern person," says Professor Needleman, "has no conception of how self-deceptive a life can be that is lived in only one part of oneself. The head, the emotions, and the body each have their own perceptions and actions, and each, in itself, can live a simulacrum of human life."

We are born, according to Gurdjieff, with an Essence, our essential self, a particularity that is determined by heredity and "planetary influences", but which is also full of promise. This promise is largely shackled by the encroachment of personality. Our habitual identification with learned personality traps us in a false self. Or rather, we're caught up in a series of false selves, scores of "parasitic identities", bullying little "I's", each "I" with its own agenda, each some facet of the distracting costume jewelry of the false personality.

If someone flatters us, one "I" takes the helm, an "I" which feels good about itself, and responds positively to the flatterer; if someone speaks ill of us, another, more resentful "I" emerges and responds angrily. We are in a "good mood" if "good" things happen to us; a "bad mood" or "depressed" when we get negative input. We have no truly consistent being. Each bullying "I" is like a program, a software engaged in running a specific response that has been triggered by specific input. Our disconnectedness with our actual, essential self prevents us from truly waking; our state of waking-sleep keeps us reacting mechanically to stimuli, squandering energy on dreaming that could be used to nurture higher levels of being.

As Needleman puts it, "There is no authentic I am in [man's] presence, but only an egoism which masquerades as the authentic self, and whose machinations poorly imitate the normal human functions of thought, feeling and will... Man identifies— that is, squanders his conscious energy, with every passing thought, impulse, and sensation... a continuous self-deception and a continuous fear which are of such a pervasively painful nature that man is constantly driven to ameliorate this condition through the endless pursuit of social recognition, sensory pleasure, or the vague and unrealizable goal of 'happiness'."

We snuggle into our slumber under the

blanket of our cherished, socially reinforced

illusions. The illusion of

self-determination, of freedom, of

wakefulness, is maintained thanks partly to

the presence of what Gurdjieff calls

buffers—"They are created," Gurdjieff

avers, "not by nature, but by man himself,

although involuntarily. The cause of their

appearance is the existence in man of many

contradictions; contradictions of opinions,

feelings, sympathies, words, and actions. If

a man throughout the whole of his life were

to feel all the contradictions that are

within him, he could not live and act as

calmly as he lives and acts now. He would

have constant friction, constant unrest...If

a man were to feel all these contradictions

he would feel what he really is. He would

feel that he is mad... Buffers are created

slowly and gradually. Very many 'buffers' are

created artificially through 'education'.

Others are created under the hypnotic

influence of all surrounding life... It is

very hard to live without 'buffers'. But

they keep man from the possibility of inner

development because 'buffers' are made to

lessen shocks and it is only shocks that can

lead a man out of the state in which he

lives, that is, waken him. 'Buffers' lull a

man to sleep, give him the agreeable and

peaceful sensation that all will be well,

that no contradictions exist and that he can

sleep in peace. 'Buffers' are appliances by

means of which a man can always be in the

right. 'Buffers' help a man not to feel his

conscience... "

We snuggle into our slumber under the

blanket of our cherished, socially reinforced

illusions. The illusion of

self-determination, of freedom, of

wakefulness, is maintained thanks partly to

the presence of what Gurdjieff calls

buffers—"They are created," Gurdjieff

avers, "not by nature, but by man himself,

although involuntarily. The cause of their

appearance is the existence in man of many

contradictions; contradictions of opinions,

feelings, sympathies, words, and actions. If

a man throughout the whole of his life were

to feel all the contradictions that are

within him, he could not live and act as

calmly as he lives and acts now. He would

have constant friction, constant unrest...If

a man were to feel all these contradictions

he would feel what he really is. He would

feel that he is mad... Buffers are created

slowly and gradually. Very many 'buffers' are

created artificially through 'education'.

Others are created under the hypnotic

influence of all surrounding life... It is

very hard to live without 'buffers'. But

they keep man from the possibility of inner

development because 'buffers' are made to

lessen shocks and it is only shocks that can

lead a man out of the state in which he

lives, that is, waken him. 'Buffers' lull a

man to sleep, give him the agreeable and

peaceful sensation that all will be well,

that no contradictions exist and that he can

sleep in peace. 'Buffers' are appliances by

means of which a man can always be in the

right. 'Buffers' help a man not to feel his

conscience... "

It's astonishing how little of ourselves we feel, even physically. We live in our body and normally sense it very little, in any conscious way. And it's correspondingly amazing how much transpires emotionally and instinctively in us, which we normally do not feel. Most psychologists agree we are driven by unconscious impulses; many acknowledge a "script" driving our responses—but do we sense these patterns in ourselves? The primary forces behind the way we live our lives are cut off from us, under prevailing conditions. Without making a conscious, finely directed effort to objectively, consistently observe ourselves inwardly and outwardly—self-observation, Gurdjieff called it—we are blind to the very forces that define us. According to Gurdjieff each of us is formed around something he called the Chief Feature, the organizing principle of the personality, and a primary obstacle to awakening. This is a big characteristic, an overall pattern coloring all our behavior, which is often perfectly obvious to our friends and family but—no matter how many times we're told about it—entirely opaque to us. It's our most obvious feature—and we're numb to it!

No matter how supposedly introverted we are, the likelihood is we know ourselves scarcely at all.

Our buffer-hidden contradictions, our mechanicality, our self-concealment—these phenomena could explain a great deal of our swept-along, baffling and violent lives.

But is there something else? Is there somewhere within us an inner connection to the cosmos, some hidden node of real consciousness, the organizing principle of a Man without quotation marks? And how do we reach it? We're told that certain, persistent longterm efforts, through a variety of methods prescribed by Gurdjieff, can create a higher self that is a vehicle, a worthy throne, for the deathless I. It's said we can formulate, like an oyster making a pearl, a conscious self that can rise above mechanicality. Man survives death only to the extent this "I" has been created. Otherwise, at death, we're absorbed back into the basic stuff of the universe, and a particular bandwith of energy—which it is our role, along with all living organisms, to transform—is then utilized by certain levels of the living cosmos as part of a cosmic ecology.

"You got to serve somebody," Bob Dylan sang. One can go with the general current, manifesting a semiconscious existence, generating a crude grade of energies to be used by the cosmos on one level—or one can choose the harder Way, to try to be, to consciously evolve, and move toward the capacity to receive and to generate a finer energy, in a higher service to the forces of creation. Either way, nothing is wasted— which idea dovetails with scientific observations of nature: Everything, in nature, is "food" for something; everything is utilized.

Gurdjieff recognizes seven general types of Man—Man Number Seven is almost unimaginably evolved relative to us. He defines four levels of consciousness: 1) what we usually call sleep, 2) our normal state of so-called waking consciousness, 3) self consciousness—characterized partly by constant "self-remembering," and a capacity to act with non-mechanical independence—and 4) objective consciousness, the level of enlightened, transcendent Being.

To pursue awakened, independent Being is harrowingly difficult. One needs a relentless will to work, rooted in an inexhaustible Wish, a hunger to learn to be - and, even that is not enough. One also needs help from others. And there's worse news yet: authentic help is hard to find, since few in our world are awake. Few have created real I. We live in a world of sleepwalkers, and it shows. As James Moore puts it, "We are all asleep. This is not a metaphor but a fact. It is also a social perception more subversive and revolutionary than anything remotely conceived by all the Troskys and Kropotkins of history; an idea which, like death and the sun, cannot be looked at steadily - a world in trance!"

We are, at least, given a glimmer of the possibility of breaking the trance in the spontaneous episodes of self-remembering we have all experienced; we've felt it in moments of danger, extreme novelty, intensity, bringing the unforgettable impression of "I'm here!" Suddenly, for a split second, we are to some extent... awake. "It is Gurdjieff's demand," says Moore, "that we acclimatize ourselves, by slow degrees, to living at this altitude. "A man may be born, but in order to be born, he must first die, and in order to die he must first awake.""

Perhaps one step in this process of "dying", is to recognize one's current state of relative non-being. If we're not conscious, are we really here, in any important sense? How often are we really conscious? We all have the experience of starting off on an errand—and simply finding oneself there, completing the errand, with no memory of the trip in between. Where were we, in the interim? In daydreams, in identification with some private dilemma— gone. One aspect of the Gurdjieff work is the simple perception of the weakness of our being, as dramatized by our tendency to lapse into non-consciousness. Go on an errand, try to stay conscious the whole time—to be there, completely—and you'll find you can't do it without a lapse. Not consistently, even for three minutes. The realization of the weakness of one's own attention is startling and instructive. To perceive it—to take it in fully and objectively—is to gradually build sections of a bridge of knowledge within oneself, across which a degree of higher consciousness might eventually travel. Or so it is said.

So far as I can discover, most esoteric work involves special efforts of attention; in the Gurdjieff work attention is directed outward to the external life and simultaneously inward to the inner world. One's inner life is normally in chaos and imbalance; with a special work of attention it can by degrees become unified.

Gurdjieff provided numerous techniques to this end—such as a form of sacred dance called the Movements, and an infinitely refinable discipline of meditation—which I am not qualified to discuss.

Our struggle to be takes place at the bottom of a scale of being. We are at the ass- end of the cosmos, Gurdjieff tells us, a place in the scale of the cosmos virtually dense with restrictive laws. Farther up the cosmic scale, up steps corresponding to the harmonic scale, we eventually come to the Absolute, the allness, the prime mover, subject to only one law: unity. In the next world down, the level of all worlds and galaxies, there are three orders of cosmic law; in the next, designated All Suns, there are six; in the next, at the level of the Sun, there are twelve; at the level of the planets, twentyfour; at the level of our own woebegone world, fortyeight orders of laws. Because we live "under fortyeight laws" we are far from the will of the Absolute, according to this system. We move toward the Absolute, toward liberation, by transcending the mechanical laws shackling us. The seven levels of the Ray of Creation are seven levels of matter; each level has its own rate of vibration. The Absolute vibrates most rapidly and is least dense; our level vibrates slowly, through a murky density.

I recently heard an astrophysicist say that at the beginning of Creation, before the Big Bang, there was, indeed, Unity, one law, or two - afterwards a sort of fractured symmetry led to the creation of the four forces, gravitation, electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force and the weak nuclear force, and all the laws proceeding from the interaction of those forces: the closer you get to the beginning of Time, the fewer laws; the farther away, the more laws.

Gurdjieff—or his teachers—anticipated much of quantum physics. For example, these Heisenbergian remarks from Gurdjieff in 1915: "Matter or substance presupposes the existence of a force or energy. This does not mean that a dualistic conception of the world is necessary. The concepts of matter and force are as relative as everything else. In the Absolute, where all is one, matter and force are also one. But in this connection matter and force are not taken as real principles of the world in itself, but as properties or characteristics of the phenomenal world observed by us."

Giving further definition to Gurdjieff's cosmology is the Law of Three and the Law of Seven. I haven't got space (in more sense than one) to do more than hint of them here. The Law of Three breaks down all events into three forces: active, passive, and neutralizing. The Law of Seven provides a systematization of the course of movements of force through a series of events. Movement of force up or down the scale through the seven "notes" of the corresponding harmonic scale can proceed only if given "shocks", conscious impetus at specific intervals, but is usually lawfully deflected by countervailing forces at predictable places along the scale. Hence the best laid plans of mice and men often go awry. That is, in Gurdjieff there's a meaning, to everything, including failure. Nothing is meaningless, seen in the perspective of the scale of things; everything is useful to the cosmos.

There are various counterfeit "Gurdjieff groups" and "Gurdjieff Centers" offering a franchised variety of "liberation"—including one that "e;begins"e; with asking for ten per cent of your income. From what I can find out, these outfits are highly suspect.

So far as I can judge, only one clearly authentic transmission of Gurdjieff's teaching exists, and its transmitters can be reached in San Francisco, New York, Paris, and many other major cities. This is the Gurdjieff Foundation, established after his death by such luminaries as Jeanne de Salzmann—who was Gurdjieff's greatest student—and others who worked with closely with him.

The Gurdjieff work is daunting. Not that anyone mistreats you, at least at the Gurdjieff Foundation - by all reports they are gentle, compassionate people, who do not exploit or abuse students. But the inner work itself, the process of awakening, is lengthy and is said to be sometimes painful (although not harmful); it involves, among other things, seeing oneself as one really is, and abiding in "conscious suffering": that is, what one suffers, one suffers consciously. Moreover, the world itself is apparently designed to discourage awakening; to place seemingly endless obstacles in the way. One of Gurdjieff's aphorisms goes, "Blessed is he who has a soul, blessed is he who has none, but woe and grief to him who has it in embryo."

You might prefer to sleep.